What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago tiday?

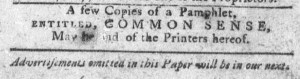

“That much esteemed Pamphlet, intitled, COMMON SENSE.”

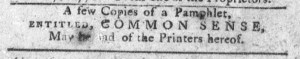

Two months after Robert Bell published the first edition of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense in Philadelphia, printers in other cities and towns in New York and New England published local editions that increased the circulation of the popular political pamphlet. Advertisements for Common Sense proliferated as those printers marketed their editions and other printers and booksellers acquired copies that they sold in their communities. On March 13, 1776, an advertisement for Common Sense appeared in the Connecticut Journal, published in New Haven, for the first time.

“Just published & to be sold by the Printers hereof,” Thomas Green and Samuel Green announced, “That much esteemed Pamphlet, intitled, COMMON SENSE; ADDRESSED To the INHABITANTS of AMERICA.” The Greens, however, had not published their own local edition. As was the case with so many other advertisements for books and pamphlets, eighteenth-century readers knew to separate the phrases “Just published” and “sold by the Printers hereof.” The latter did not mean that the printers had published the pamphlet themselves; instead, it meant that the pamphlet was “now available” rather than “forthcoming” or “in the press.”

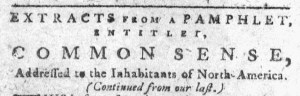

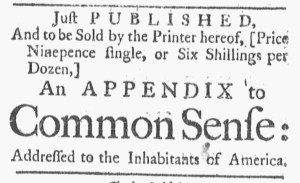

The Greens stocked an edition that included “an APPENDIX to Common Sense, and an Address to the Representatives of the People called Quakers.” Paine included that additional material in his approved new edition published by William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, the printers of the Pennsylvania Journal, after he parted ways with Bell. It did not take long for Bell to pirate those items and incorporate them into a supplementary pamphlet of essays he marketed as related to Common Sense. On the same day that the Greens first advertised Common Sense in the Connecticut Journal, the Bradfords once again cautioned the public that the “Pamphlet advertised by Robert Bell, entitled Additions to Common Sense … consists of pieces taken out of the News-papers, and not written by the author of Common Sense.” That the Greens did not mention any additional material except the “APPENDIX, and an Address to the Representatives of the People called QUAKERS” suggests that they stocked copies published by the Bradfords rather than by Bell. The advertisement does not definitively demonstrate that was the case, but it does show that more and more printers made some version of the political pamphlet available to readers. The Greens simultaneously advertised “EXTRACTS from the VOTES and PROCEEDINGS of the American CONTINENTAL CONGRESS,” supplying customers with other products to keep informed beyond what they read in the newspaper.